In school, I took physics and wondered if I would ever use any of the scientific stuff. All of that stuff is kind of important if you want to know how altitude can affect the performance of a vacuum brake booster engine, your body and a whole lot of other devices.

Feeling the Pressure

In science and design, there is a need to convert barometric pressure into a dimension that can be used to measure the force of atmospheric pressure. Atmospheric pressure can be converted to 14.7 pounds per square inch of pressure at sea level.

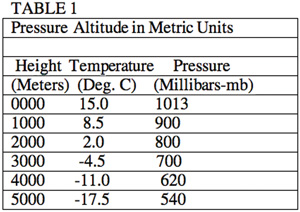

In 1929, atmospheric pressure was given a scientific unit of “bar.” One bar is equal to 14.504 pounds per square inch. Table 1 shows how atmospheric pressure changes with altitude and temperature.

Today, the Pascal (Pa) is the scientific unit to measure barometric pressure. One bar is equal to 100,000 Pascals or 100 Kilo Pascals (100 Kpa). This is unit of barometric pressure used in the scan tool.

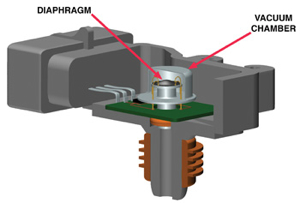

Since the 1980s, a barometric pressure sensor (Baro sensor) or a Manifold Absolute Pressure (MAP) sensor is used to measure barometric pressure for engine emissions control. This information can be shared with other controllers on the CANbus.

Figure 1

The MAP sensor is actually a Baro sensor attached to the intake manifold. When the ignition is turned on, the controller measures barometric pressure and stores it in its memory. The controller then measures the differential from atmospheric pressure to manifold pressure. The MAP and Baro sensors are constructed of a vacuum chamber and diaphragm that is

connected to the intake manifold.

The differential in pressure between the vacuum chamber and manifold vacuum changes the resistance of the diaphragm and voltage signal to the controller. See Figure 1.

The area of a circle is calculated as A=pi X r2 or (A= 3.14 X r X r)

Area of a Circle

Applying the Scientific Stuff

Atmospheric pressure and engine manifold vacuum are the two factors that make a brake booster work. The pressure differential created on either side of the diaphragm(s) in the booster produces a force on the piston of the master cylinder. If engine manifold vacuum is 20 inches Hg or 68 Kpa at sea level, the booster is capable of exerting 9.8-PSI ± 0.5 PSI on the diaphragm of the booster.

For example, there are 53.6 square inches of surface on an 8.5-inch booster diaphragm. By multiplying the surface of the diaphragm X, the pressure available would equal total output of 525 pounds of force on the master cylinder pistons at a 100% apply of the booster.

As altitude increases, barometric pressure is reduced. Zero atmospheric pressure occurs at approximately 30 miles or 158,400 feet above sea level. In Denver CO, atmospheric pressure is 17% less than at sea level.

Table 1 shows how atmospheric pressure changes with altitude and temperature. If a vacuum-assisted brake booster is rated at 100% efficient at sea level, its efficiency is reduced by 17% at the Capitol building in the “mile high city.” So, in Denver, it would be 436 pounds of force at atmospheric apply.

Most stops use approximately 20 to 40% of the atmospheric pressure differential to stop the vehicle. A stop from 30 mph requires 20% of an atmospheric apply in Denver, which would equate to 87 pounds of force on the master cylinder pistons. The 87 pounds of force transferred a 0.75 (19mm) master cylinder piston would equal 38 psi of hydraulic pressure.

As you have learned, the area of a circle is calculated as A=pi X r2. As, the hydraulic pressure is applied to calipers with 2” (50.8mm) diameter, this would generate 119 pounds of force on the brake pads.

Torricelli’s Contribution

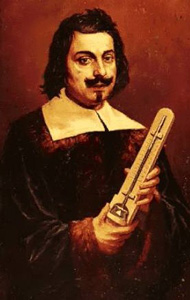

Atmospheric pressure is measured as a differential between a vacuum and the atmosphere. In 1643, Evangelista Torricelli invented the barometer by filling a 4-foot-long glass tube with mercury (Hg), sealing it at one end, and inverting it in a dish of mercury. Some of the mercury flowed out of the tube, but in the space that remained, a vacuum was created.

Torricelli

Experimenting over time, Torricelli found that the height of the column of mercury in the tube was subject to fluctuations. He correctly concluded that these fluctuations are the result of variations in the pressure exerted by the atmosphere, and that it was atmospheric pressure that supported the column of mercury in the tube.

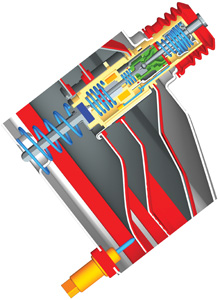

Booster Types

There are two types of booster units. The most common is the single diaphragm used for compact vehicle applications. It has a single vacuum and pressure chamber. The tandem is the second type of unit and is used for full-size vehicles, light trucks and SUVs. See Figure 2.

The tandem uses three diaphragms to form two vacuum and pressure chambers.

Operation Modes

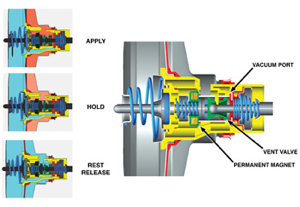

There are four modes of operation for a vacuum brake booster during a brake application. They are rest, apply, hold or balance, and release. In apply mode, the pressure from the brake pedal causes the push rod to move the treadle valve forward and close the vacuum port to the vacuum diaphragm chambers and

isolate the vent valve.

As the push rod continues to move forward, it opens the vent valve to atmospheric pressure. This pressurizes the boost chamber(s) to create a force on the diaphragm(s), power piston and the push rod connected to the master cylinder pistons. In hold or balance mode, the pressure generated by the brake pedal push rod and pressure from the master cylinder piston push rod equalize. This causes the treadle valve to close the vent valve.

Figure 2

Release and rest mode are the same. When the pressure generated by the pedal is released, the vacuum valve opens, the pressure from the boost chamber(s) is evacuated, and the power piston is returned to its rest position by the spring in the main vacuum chamber (Figure 3). The vacuum check valve is a key component to the operation of the booster.

A leak in the valve can cause a reduction in the performance of the booster and increase pedal travel. A manifold vacuum of 20” Hg or greater can be achieved during engine deceleration. The booster chambers can be evacuated and retained at this pressure by a properly operating check valve.

Did You Know…

Anti-lock Brake systems (ABS) and Electronic Stability Programs (ESP) will function at their best when full vacuum boost is applied.

Bolstering the Booster

In an emergency stop where the brake pedal is rapidly depressed, the vacuum booster may not be able to react fast enough to apply adequate force to the master cylinder in an effort to provide the shortest stopping distance.

Figure 3

In an effort to combat this issue, Brake Assist Systems (BAS), which utilizes a mechanical or electromechanical function to apply a 100% vacuum/pressure assist, were developed. For the most part, BAS detects circumstances in which emergency braking is required by measuring the speed with which the brake pedal is depressed. It is often used as an enhancement to ABS, Electronic Stability Programs (ESP) and Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC).

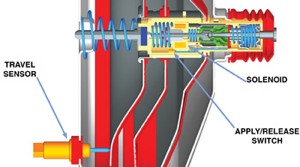

The Continental Teves-developed unit is used on full-size vehicles. It uses a brake apply/release switch, diaphragm travel sensor and a solenoid winding.

The brake apply/release switch closes when the brakes are applied. The diaphragm travel sensor measures the speed at which the brakes are being applied. If a rapid/emergency brake apply is sensed, the BAS controller will energize the solenoid winding to increase the apply pressure on the master cylinder push rod.

This BAS is active at speeds above 5 mph and there are no fault codes present in the controller. The TRW Mechanical Brake Assist (MBA) uses a permanent magnet to engage maximum assist for emergency stops in a single diaphragm unit as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

BAS With ACC

ACC systems use a radar sensor to calculate the distance between the ACC vehicle and vehicle traffic. A vehicle’s ACC system will match the speed of the vehicle ahead of it by reducing the throttle and/or applying the brakes automatically.

The BAS unit can used to implement ACC braking. Other methods can use a pump to supply a hydraulic brake apply. In the case of the BAS, the ACC will send a message to the BAS controller and it will activate the solenoid and apply and release the brakes.

A change in throttle position from the driver will also disengage the auto braking function. When the driver throttle input is released and cruise speed is resumed, the auto braking function is reactivated.